- Home

- Yukiko Motoya

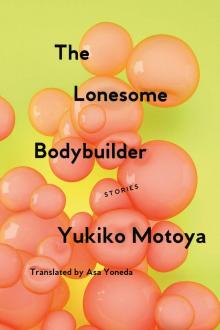

The Lonesome Bodybuilder Page 4

The Lonesome Bodybuilder Read online

Page 4

“You’ve got to be joking. A roomful of grown men put their heads together and this was all you could come up with? I can’t believe you’re actually getting paid for this shit.”

Maybe it’s like this. Sad people like me are on the rise because of numbskulls like you who blow up like balloons without a single thought for the consequences. You get all our hopes up. We think, This time, this time, I’ll find someone for sure. But because you’re never there, we have to learn to be pragmatic, explain things away rationally. Sure, there might be other things that teach us to do this, but the first betrayal each of us goes through is at the hands of a bulge in a curtain. At least it was that way for me. You were the very first to let me down. You imprinted me with some kind of habit for being betrayed. Men keep lying to me and abandoning me. No matter how devoted I am to them. You’re where it all starts.

“Put down your markers this instant and eat some chocolate. Get your blood sugar up. Eat until you come up with some ideas.”

Why don’t you show yourself already? You can’t possibly think people are going to keep looking for you forever? I was sick and tired of it all. I wanted to get to a world where there was only yes or no. Ones and zeros.

“Eat, then write. Squeeze some ideas out of your sorry brains. Get on it!”

When I looked again, the bulge in the curtain—unless it was my imagination?—had shrunk a little. Wait. You’re leaving? Without a word? Just because I told you how I really felt? That’s exactly what I mean when I say you’re unfair. Wait a second. I didn’t mean it. Don’t go. I don’t have the strength to make it through this life on my own. Why do you all try to leave me? You’re not even there anyway, are you? Of course you aren’t. In which case the least you can do before you go is listen to the story of my first time. I was in third grade when I first found you all swollen up. Upstairs, in my room. Just after lunchtime, during summer vacation. Both my parents were out. I was rearranging posters on the wall, trying out one unsatisfactory layout after another. At first I thought you were a trick of the light. When I came closer timidly and touched you, it even seemed like you got a little bigger, right there in front of my eyes. See, it’s starting to come back to you, isn’t it? Right away, I ran out to the garden and looked up to the second floor to check on you through the window. But there was no one inside. I even climbed out onto the roof, but it made no difference—I still couldn’t see anyone.

I was scared at first, but I also sensed that you were a presence that would protect me, so I let you stay. You lived with me for twenty days. I got to know you enough to wish you sweet dreams every night, and since I couldn’t use my curtains, I set up a cardboard box to keep the sunrise from disturbing us. Huh, I guess I was already desperate to make people stay, even back then.

Our parting came suddenly. One day, I went into my room to find the edge of the curtain, which I’d carefully tied back, undone, and the curtains firmly closed. It was my own fault, for keeping our relationship a secret from my mother. I rushed to open them, in tears, thinking you’d left me without even a word. We’d spent twenty days together, but there was no one there. Just the lace curtain puddled in the corner, like a shell you’d discarded. I called out your name. That’s right. I’d given you a name.

Never mind. It’s too painful remembering the way I used to be. Back then I never bothered with boring explanations. My mind was open to anything. I wasn’t worried about being disrespected by my team, or of people thinking I was a crazy woman. I didn’t let myself be bound by anything as common as common sense.

I looked at the whiteboard and saw the colorful ideas that my men had scrawled onto it, all overlapping each other. There was no way I could decipher who had written what. Ugh. Were they all idiots? Feeling that I’d just remembered something precious, I drew three black dots on the back of my handout, and chuckled.

“Hey, come look at this. It looks like a face, even though all I did was go dot, dot, dot!”

My team leaned in and peered at the sheet.

“Is everything okay, boss?”

“Are you feeling all right?”

I got out of my chair, gave them a cute little wave when I reached the door, and put the conference room behind me. I skipped down the long tiled walkway we complained about having to walk down in heels to go buy lunch, and broke into a sprint, rounding a corner shouting, “Ch-ch-chaaaaaaaaarge!” I looked over my shoulder and there, on the face of a high-rise, I saw three yellow window-cleaning platforms suspended in midair. When I realized they were positioned precisely like those three points I’d drawn earlier, I nearly peed myself. I knew that someone—someone very big—had found me. It’s about time you finally turned up, I said to him as the tears rolled down my face.

An Exotic Marriage

One day, i realized that i was starting to look just like my husband.

It wasn’t that someone pointed it out. It occurred to me by accident, while I was sorting through some files that had accumulated on the computer, comparing photos from five years ago, before we were married, to more recent ones. I couldn’t have described how, exactly. But the more I looked, the more it seemed as if my husband was becoming similar to me, and me to him.

“The two of you? I can’t say I’ve noticed it,” my brother, Senta, said when I mentioned it. I had called him to get help with the computer. He spoke in his usual slow way, like a languid animal resting by water. “You must have just adopted each other’s expressions from spending a lot of time together.”

“By that logic, you and Hakone should look even more alike,” I said, double-clicking on a folder as he’d instructed.

Senta and his girlfriend, Hakone, had started dating in their teens, so they’d been together twice as long as my husband and I. We’d gotten married a year and a half after we met.

“Being married must be different from just living together,” he said.

“Different how?”

“Dunno. More . . . concentrated?”

Senta directed me to drag the folder containing the photos over to the icon of the camera.

“I’ve done this before,” I said. “Every time I try, it goes boinng! right back to where it came from.”

As expected, I had to contend with the boinng! at least twice, but eventually managed to back up the photos. I told him we were thinking of selling our refrigerator on an online auction site soon and asked him to think of any tips, and then we hung up.

I took a package to the post office for my husband. On the way back, I saw Miss Kitae sitting on a bench inside the dog run. When I knocked on the glass, she looked up and beckoned to me, so I decided to stop in for a minute.

Our apartment complex had a private dog run. It was a small park that had been created by decking over the top of the roof that extended over the entrance, and could be accessed from the hallway on the second floor. I pushed open the heavy steel fire door.

“San, dear, over here,” Kitae said, patting the empty space next to her on the bench. “Visit with me for a bit. I know you’re not busy.”

She pulled her customized shopping cart toward her and passed me a canned coffee from the rear pocket. Her beloved cat, Sansho, was on a string leash and curled up on a cushion on top of the cart like a piece of decor, as usual. Kitae brought Sansho out to sun in the dog run every day after lunch, saying it was only fair, since she paid the same rent as our neighbors who had dogs. Kitae was nearly thirty years older than I was, but she exuded health and had a marvelously straight back. Her skin was so dewy she could have easily been mistaken for someone in her fifties, if not for her gray hair. She pulled off white jeans better than I could ever hope to.

I had first met her in the waiting room at the veterinary clinic I took my cat to, where she’d confided in me at length about Sansho’s toilet problems. Our apartment complex was a large one, unusual for the area, with two wings, a west wing and an east wing. The resident turnover was quite high, and most of us didn’t socialize with our neighbors.

Kitae was probably the only one I could claim to know. At first, I’d kept some distance from her strange habit of dragging her cat outside against its will, but as she kept greeting me, I gradually started to get to know her, partly out of interest in Sansho, who always lay unmoving on the cushion like a stone statue.

I sat down next to her and pulled up the tab on the canned coffee. “What a nice day,” I said, even though the humidity was making my T-shirt cling damply to my skin.

“I can’t stand the Japanese summer. So wet and miserable.” Kitae looked across the sunny wooden deck and pulled an exaggerated grimace. Before moving here, she and her husband had lived in an apartment in San Francisco. She’d told me recently that they’d bought it when they were still young. When its value had skyrocketed, it had been good news—until their property taxes went up too, and they’d had no choice but to sell up and come back to Japan.

Really, San, it was five million yen a year, for an apartment we’d already paid for. Five million! What a joke!

I’d seen Kitae’s husband around just once—my impression of him was of a gentle man smiling while he listened to Kitae talk, like a jizo statue, or Sansho.

Kitae asked after anything exciting going on in my life.

“I’m starting to look like my husband.” I found myself telling her about the photos.

She stopped waving the hand she’d been using as a fan and said, “Dear me,” displaying an unexpected level of interest. “Tell me again how long you’ve been married.”

“Coming up to four years.”

“Now, I could be wrong—I haven’t known you long enough to say—but you should be careful. You’re accommodating, San, and before you know it, girls like you get all—”

A corgi running around on the deck barked at a butterfly, and I missed the end of Kitae’s sentence. I hoped she might repeat herself, but she was too busy lifting up her bangs with one hand while flapping the other to cool herself.

“Show me those photos next time,” she said.

“I will.”

Kitae pulled her cart over to scratch Sansho under his jaw. It seemed like a good time to leave, but then she took out an individually wrapped cookie from the rear pocket of the cart and started talking again.

“A married couple I know,” she said, and I nodded and hurriedly sat my bottom back down firmly on the bench. Her story, which she told me while breaking the cookie into pieces, went like this.

There was once a husband and wife. Of course, Kitae knew their names and faces—they were old friends of her and her husband’s. The two couples had socialized together, but after Kitae and her husband had moved to San Francisco, they didn’t get the chance to meet again until nearly ten years later.

During those ten years, the other couple had moved to England. Kitae visited London and arranged to meet up with them. When she arrived at the restaurant, they stood up to greet her—“Long time no see!”—and Kitae was astounded at what she saw.

“They’d grown identical, like twins,” she said, closing her eyes as though she were recalling the sight.

“Did they resemble each other to begin with?” I asked.

“That’s the thing. They’d been nothing like each other. Which was why I wondered, just for an instant, whether they’d had plastic surgery.”

During the meal, Kitae tried to compare the couple’s faces, looking discreetly from one to the other. She considered that it might have been the result of their aging, but the degree to which they’d changed couldn’t be put down solely to the effects of time. Plus, and this was very strange indeed, when she considered the individual features separately—eyes, noses, mouths—the two of them were clearly different people. But the moment she saw their faces as a whole, somehow they seemed like mirror images. Kitae felt uneasy, as though she were being duped.

“Was it the way they ate? Their mannerisms or their body language?” I accepted a piece of cookie.

She leaned her head to one side, thinking. “Maybe that was part of it. But it was more that there was something drawing them closer. As if they couldn’t help but imitate each other.” She frowned.

The even more surprising thing was that the wife was tucking happily into platters of oysters and lobster, which she’d disliked years ago. As far as Kitae could recall, it had only been the husband who’d had a fondness for those things. When she casually brought that up, the wife said, “What? Really?” and looked startled. After a while, she said, “That’s not true. I’ve always loved oysters,” and turned to her husband. “Isn’t that right?”

Beside her, the husband nodded in agreement.

They finished their meal before Kitae’s foggy doubts had cleared.

“We promised to see each other again soon, but then . . . ,” she said, poking a piece of cookie toward Sansho’s nose.

“It didn’t work out that way?” I said.

“No,” she said. “The next time we met was another ten years later.”

Kitae turned up at the same restaurant, where they’d arranged to meet again, feeling a little nervous. When they stood up from their chairs and turned toward her, she exclaimed to herself in surprise. Even from a slight distance, she could see that they’d reverted to their original, un-like, separate selves.

“I felt almost cheated,” Kitae said, munching a piece of cookie in which Sansho had shown no interest. “Because a part of me had been hoping they’d have become even more alike.”

The three of them finished their meal and headed toward the main street to find a taxi. Kitae looked at the husband’s back as he walked ahead and, suddenly feeling laughter bubbling up, turned to the wife and confessed what had been on her mind for the last ten years. “I don’t know what got into me. I guess I imagined it.”

The couple invited Kitae back to their place and drank wine until the husband passed out. After Kitae and the wife had emptied their third bottle, the wife said, “Kitae, darling, why don’t we step out and have a look in the garden?”

Kitae had been gazing at the rocks that were placed around the house, thinking the display was in peculiar taste. She got up and followed the wife outside unsteadily. In the moonlight the wife made her way through the English-style garden and crossed a small bridge over the pond. Eventually, she stopped in front of a flower bed blooming with salvia.

“I’m going to let you in on a secret, about how I got back to the way I was,” the wife said. It must have been the wine that made her sound like she was trying not to giggle.

“What are you talking about?” Kitae asked.

“I mean how I got back to myself. You’d like to know, wouldn’t you? That’s the secret,” the wife said, and pointed to the side of the flower bed.

“A rock?” The moonlit flower bed was strewn with fist-size stones similar to the ones inside the house.

“Exactly. My stand-ins.” The wife told Kitae to pick one up.

Doubtfully, Kitae crouched and chose one. Like the ones inside the house, it was a lumpy, thoroughly ordinary rock. “What about it?” Kitae asked, impatient.

“Look closer,” the wife said. “You’ll see that it’s nearly a perfect likeness.”

“Likeness? To what?”

“You’ll see it. Just look.”

Kitae stood up and looked at the rock in the moonlight. She half thought she was being played for some kind of joke, but when she changed the angle of the rock slightly, she felt her tipsiness evaporate.

“Incredible,” she said softly. There was the nose, the eyes—the resemblance to the husband was remarkable.

“Isn’t it?”

The wife explained that it had all started with the stones in the flower dish she’d put by their bedside. “They’d get to look so much like him, and I had to keep swapping them out. They just kind of piled up.” Only then did Kitae notice that there were countless rocks of a similar size by the side of the salvia bed.

I let out a breath. “It reminds me of the story of the three

talismans.”

“How does that one go?” Kitae tilted her head to one side.

“Wasn’t it about a monk who was nearly devoured by a mountain hag, and stuck a talisman on a pillar in the lavatory to take his place?”

Kitae said, “Right,” though I couldn’t tell whether she was interested or not. She got up, saying, “She asked me whether I wanted to take one as a souvenir, but I couldn’t. It would have been just a little too peculiar, don’t you think?”

We were the only ones left in the dog run. “Thank you for the coffee,” I said, and rushed to open the fire door for Kitae, who had started pushing her cart toward it. I watched for a while as she made her way across the suspended walkway toward the east wing, and then made my way back to the west wing.

Back in the apartment, I picked up around the living room and switched on the Roomba.

What with the built-in dishwasher doing the dishes after breakfast, and the washing machine drying the laundry too, I sometimes got confused about who did the housework around here. Before I was married, I’d had an office job at a water cooler company. The company was small and understaffed, and when I met my future husband the workload was taking a toll on my health. I only found out his earnings were more than average after we started dating, but when he told me I shouldn’t keep working if I didn’t want to, I leapt at the opportunity. Since then, though I called myself a homemaker, I felt a lingering guilt about just how easy I had it. Owning a home at this age, I felt as if I’d somehow managed to cheat at life. I almost wished for a child so I could have a good reason to stay at home, but—perhaps because my motives were impure—there was no sign of us conceiving anytime soon.

The Lonesome Bodybuilder

The Lonesome Bodybuilder